Editor's Note: Starting in 2023, the EFC (expected family contribution) is going away, and being replaced by the Student Aid Index (SAI). See our full SAI Chart and SAI Calculator here >>

If you’re hoping to receive a substantial amount of need-based financial aid for college or graduate school, your Expected Family Contribution (EFC) will be one of the most important numbers you’ll ever see. (Need-based financial aid is financial aid you receive because you couldn’t afford college otherwise; “merit-based” financial aid doesn’t depend on your family’s financial situation, but is based on other factors like your academic, athletic, artistic, or service achievements.)

After you’re admitted to your dream school, a complex set of gears grind into action. First, each school calculates a “cost of attendance” (COA) — a number that includes tuition, room and board, and other anticipated costs like books, transportation, technology fees, and the like.

Then, based on the information you’ve provided about your family’s income and assets, the federal government and the college between them will come up with the EFC. That’s the money that you and your family are expected to pay towards your education during the next school year.

Subtract the EFC from the COA and you get the other number you’re really interested in: how much financial aid you’ll be eligible for from the government, your school, or both. (Just watch out — different schools might provide a different mix of loans vs. grants to meet that financial need, so compare financial aid offers.)

So, where exactly does the EFC number come from? It’s calculated different ways by the federal government and by some schools, but it’s all based on your reporting of: your family assets (the value of your savings or investment accounts [excluding retirement accounts] if you have them) and, sometimes, your home or business assets; your family income; the size of your family; and the number of dependent children enrolled in college.

None of these formulas, however, take debt (credit card, mortgage, or preexisting student loans) into account; they are entirely based on assets and income. And they are heavily weighted towards income, meaning that a high-income family with few assets may well end up with a higher EFC than a lower-income family that owns a house and has substantial savings.

EFC Method 1: The FAFSA

The Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, is required of every student in the United States who is seeking any kind of federal financial aid — which is to say, pretty much every student! Most colleges in the U.S. use it as their only application for need-based financial aid. Every year that you attend college or graduate school, you’ll have to file a FAFSA (typically online) and a brand-new calculation of your EFC will be made.

The EFC formula is complicated — big surprise! — because it takes a lot of factors into account. It also changes slightly from year to year. You can get a completist version of the 2023-2024 school year rules in this 29-page guide from the Department of Education.

Also on the Department of Education’s page, you can try out the Federal Student Aid Estimator — a cool little calculator tool that you can use to project possible EFCs even if you’re nowhere near ready for college. While the FAFSA4caster tool will give you an estimate, how does the formula work, for the most part, if you look under the hood?

The Department of Education uses three different formulas to calculate an EFC. Formula A is for dependent students (anyone who can be claimed as a dependent on their parents’ taxes); Formula B is for independent students who don’t have dependents other than a spouse (read: no kids); and Formula C is for independent students who do have dependents other than a spouse.

A short article isn’t going to cover all the nuances, but here’s a start that ought to cover most dependent students’ situations and at least give you a rough estimate of what your EFC might end up being.

First, in general, parents are expected to contribute up to 47% of their net income to the cost of college every year. Before you freak out, stop! That doesn’t mean 47% of every dollar you earn. (And remember, it’s cumulative, so if you have multiple children in college at the same time, it’s up to 47% for all of them combined, not for each.)

Take your Adjusted Gross Income from line 37 of your parents’ 1040 tax return form. If you’re reading this in fall 2023, you will actually want the AGI from the 2022 tax year. Add retirement plan and Health Savings Account contributions; child support; and any other income received, even if you didn’t pay taxes on it.

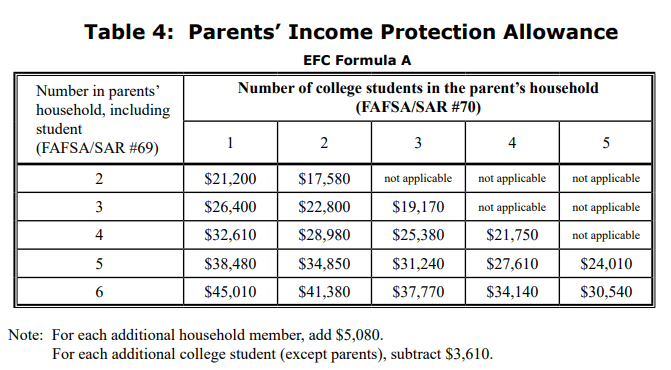

Now the number is looking really big, but this is where you get to start subtracting. You can start with subtracting your federal, state, and FICA taxes. Then you can subtract an “income protection allowance,” which varies depending on how many people are in the household and how many of them are in college (see table below).

What you’re left with is your “net available income.” Multiply it by 0.47 to get the amount you’re probably going to be expected to spend on college next year. If that’s, say, $40,000, then the aid formulas will anticipate that you can spend $18,800.

Second, the formula will look at your parents’ assets. The FAFSA isn’t interested in their retirement accounts (retirement accounts, like 401k and IRA, don't count on the FAFSA). It also doesn’t look at home equity or the assets of small businesses with fewer than 100 employees. But it does want to know what your parents have in savings, checking, and taxable investment accounts.

Get a total for this number and subtract the savings and asset protection allowance (see table) — which has dropped to zero for 2023-2024. Then multiply by 0.0564 to determine how much of these assets are expected to be available for college spending. Add this to the number from the first step.

(Note: If, like me, you went to college some time ago, you may be shocked by how few assets are protected these days. As recently as 2010, an average of around $50,000 was protected, but because of the way the numbers are calculated, the protected amount has declined really rapidly. Nothing can be done about it unless Congress acts though, so you might want to give your representatives a call.)

Third, the formula now wants to know what your income and assets are. If you have income, subtract taxes paid, then $6,600; then multiply anything remaining by 0.2. Then add up your checking, savings, and/or investment accounts, and expect to pay 20% of their value each year towards college. (Dependent students don’t get a reserve allowance, so use the full value in your calculation and multiply it by 0.2.) If you have a 529 plan (college savings account) though, multiply the value of that by 0.0564. Add this number or those numbers to those from the first two steps, and you should have something approximating your EFC — unless your family situation is unusually complex.

If you’re an independent student, the formula only considers income and assets from yourself and, if you have one, your spouse. Roughly speaking, if you don’t have non-spousal dependents, you can add up your AGI, retirement contributions, child support, etc.; subtract taxes; and subtract about $10,000 if you’re single or if you’re married and your spouse is also enrolled in college, or about $16,000 if you’re married and your spouse isn’t a student. The number you get represents your “net income,” and you’ll be expected to pay about 50% of it towards college.

If you’re an independent student with dependents other than your spouse, your EFC is calculated yet a third way. The percentage of your income you’ll be expected to contribute will vary depending on the number of dependents you have and your age, so your best bet is to use the FAFSA4caster tool on the Department of Education’s website. If you’re really curious about the details you can also work through the worksheets in The EFC Formula guide to see exactly how it works.

CSS Profile

About 200 colleges and universities in the United States ask students to file another financial disclosure using the College Board’s College Scholarship Service (CSS) Profile (in addition to the FAFSA, which they all also require).

These are schools that have their own aid money to give away; most, though not all, are highly selective and quite wealthy. The CSS Profile can never be used to determine your eligibility for federal aid. It’s only used to determine access to the college’s aid dollars.

If your school uses the CSS Profile, it’s going to ask for a lot of information about your and your parents’ income and assets — way more than the FAFSA does. And some of it may seem really irrelevant. It may not even use all of this information in its formal calculations.

For example, the CSS Profile will ask about your parents’ retirement account assets, even though it won’t expect them to spend any of that money on college. Why ask, then? College financial aid officers who use the CSS Profile say that they just want to have as complete a picture of the family’s finances as possible. This is because they have some discretion over how aid is distributed and might end up being able to give a little more to a family with strong income but low retirement savings, for example.

Because each college runs its calculation differently, it’s much more challenging to calculate your own EFC for the CSS Profile than for the FAFSA. But you can start with the idea that parents will still be expected to spend 47% of your net available income . . . however, it’s likely to be calculated based on a two-year average rather than on one year’s reporting. Schools say this lets them better take into account variable income. (That can work in your favor if you have unusually low income one of those years, or it can work against you if your income is atypically high.)

The CSS Profile formula for counting assets takes into account several factors that the FAFSA formula doesn’t. Home equity up to 1.2 times the parents’ AGI gets counted, and so do small business assets (which are ignored by the FAFSA). Add up these assets with the checking, savings, and investment accounts; subtract $20,000; and multiply by 0.05, and you’ll have a rough idea of how much of your assets you’ll be expected to spend on college.

Note that every college calculates this number differently, so you can only get a rough estimate when you do it on the back of the envelope. In particular, different colleges treat home equity wildly differently, with some not counting it at all (even though the CSS Profile asks about it) and others counting it up to as much as 2.5 times the parents’ AGI.

Students’ assets, in general, should be added up and then multiplied by 0.25. However, many schools are treating student-owned 529 plans (a type of savings plan) like parental assets, to be multiplied by 0.05 instead. But some schools do expect you to spend 25% per year of these plans. So . . . yes, it’s really hard to know in advance!

The EFC Seems . . . Really High Compared to What We Can Actually Afford

Yeah. There’s just no way around it: the EFC is, for many people, not an “affordable” number.

Keep in mind, though, that there will be a lot of other things going on as you decide what college you can afford to go to and how to make that happen.

For example, you may be able to use a 529 plan to cover part of your EFC, since you’ll only be expected to use about 6% of it every year. A cheaper college, like a community college or state school, may also help; the entire cost of attendance may be less than your EFC, which would mean that you don’t qualify for federal aid to attend that school, but could still mean that you and your parents are on the hook for far less than the EFC.

It’s true, though, that covering the gap between the EFC and what you feel you can really afford is how many people end up with unsubsidized private loans.

As always, please be careful when you’re considering private loans (or any loans!). Think carefully about how much money you expect to make when you graduate and how much your loan payments are likely to be each month.

Robert Farrington is America’s Millennial Money Expert® and America’s Student Loan Debt Expert™, and the founder of The College Investor, a personal finance site dedicated to helping millennials escape student loan debt to start investing and building wealth for the future. You can learn more about him on the About Page or on his personal site RobertFarrington.com.

He regularly writes about investing, student loan debt, and general personal finance topics geared toward anyone wanting to earn more, get out of debt, and start building wealth for the future.

He has been quoted in major publications, including the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, ABC, NBC, Today, and more. He is also a regular contributor to Forbes.

Editor: Clint Proctor Reviewed by: Chris Muller